The Candy Crush Scam That Beat GTA

Somewhere between GTA’s five-year epic and Candy Crush’s five-month sprint, gaming learned what really sells.

The way games are made is changing and not in a good way. And for now I think no story proves that better than Candy Crush.

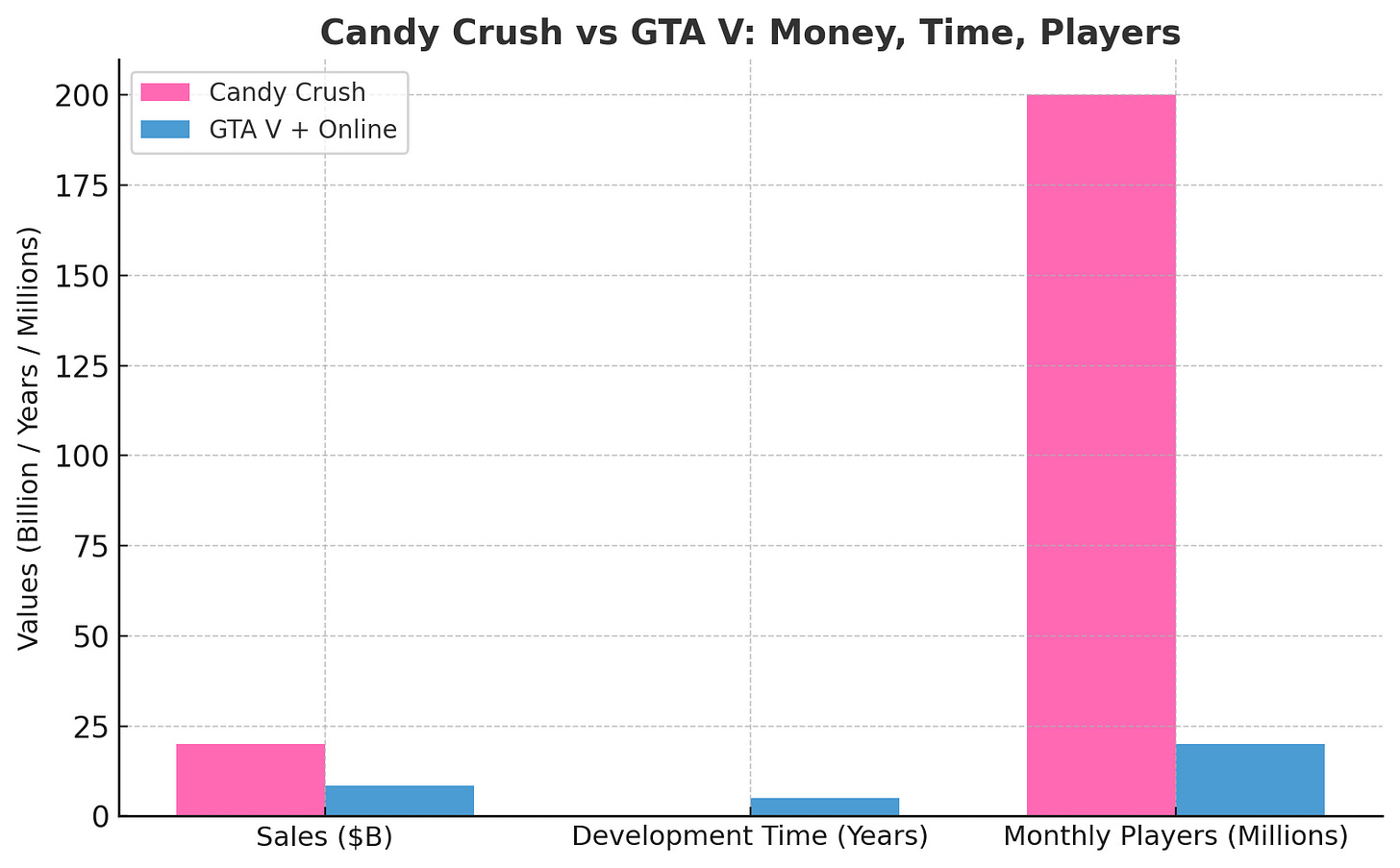

On the left is Candy Crush. It made 20 billion dollars in sales. On the right: GTA V and Online, which combined made 8.5 billion. Candy Crush took five months to make; GTA, five years. One has 200 million monthly players, the other about 20 million. Two very different games. One’s a cultural masterpiece – and the other a billion-dollar slot machine.

Now, there’s nothing wrong with gamified slot machines, until they become the blueprint for how games are made. Because if games like Candy Crush win, games like GTA stop getting made. And that’s when it gets dangerous. That’s when games stop being made with passion and start being engineered for profit.

And the men behind all that candy? A ruthless consultant. A matchmaking tycoon. And the son of Britain’s most notorious capitalist. Toby Rowland (left guy).

Meet Toby Rowland, co-founder of King and for a while, its biggest shareholder.

“My background is interesting… because I come from three generations of entrepreneurs.”

To understand Toby, you need to meet his dad, once described as Britain’s “unpleasant face of capitalism.” His dad was a corporate raider who deceived African dictators, stole their profits, and funneled the cash back to Britain. As he once famously said, “You can never have enough enemies.”

When he died, he left over half a billion pounds. And that’s the shadow Toby grew up in. Not just born into money, but born into a mindset. One where deception was the business model. And when King was born, that deception carried over.

But not without the man who quietly funded most of King: Mel Morris (the middle guy), a flooring salesman turned one of Britain’s richest men. Before King, he built uDate — the world’s second-biggest dating site — where he hired Toby as head of marketing. After selling uDate, Mel bought his hometown football club and started King.

One went bankrupt – Mel’s “fatal mistake.” The other? Make no mistakes. Because while Mel brought the cash, another brought the strategy. A consultant who could sell like a shark: Riccardo Zacconi (guy on the right).

“Inspiration can come anywhere, anytime. For example, Candy Crush was invented in the bathtub.”

Riccardo Zacconi

No, Candy Crush was NOT invendted in a bathtub. But let’s not pop Riccardo’s corporate bubble just yet. Because it was he who truly turned King into what it is today.

“We always had the ambition to grow – the ambition of ‘Hey, this is where we want to go!’”

Riccardo wasn’t a game designer, but he was a numbers guy. A reserved consultant, the banker type.

Hungry to conquer the world, he joined Mel and Toby over at uDate.

And when King was born, Riccardo became the king himself, turning Candy Crush into the game it is today – at the cost of people’s addiction.

“By the end of the month, the game skyrocketed — I never experienced anything like it. The users went up like a rocket.”

But Riccardo didn’t do it alone. Two developers in particular created the game and the data machine behind it.

Now the crew was complete. And what they built wasn’t just a game – it was an addiction machine wrapped in candy.

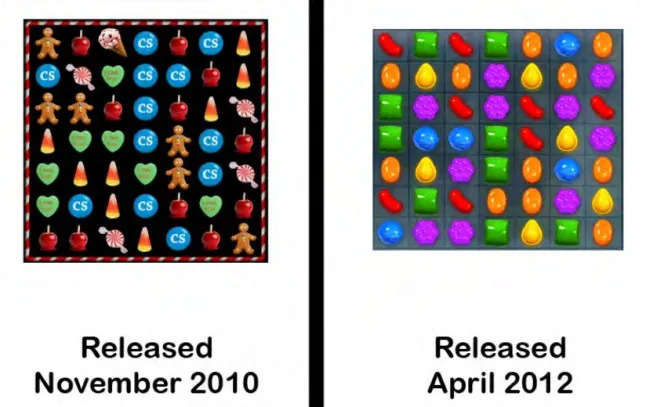

Thing is, they’d been training for this. King started out as a gambling site. Skill-based, competitive, and perfect for studying player behavior. With every click, King learned what made people play and pay.

And when Facebook and mobile gaming became a thing, King took all those lessons and built Candy Crush. Sweet, but deceptive.

The game is simple: Match candies. Clear levels. Feel good. Right off the bat, it hits you with a tutorial. Big arrows, shiny animations, flashy sounds… even the “Next Level” button jiggles to get your attention.

Every level has clear goals: collect a certain amount of candy. The first levels are so easy, I didn’t have to do anything — the game was playing itself. But the more I progressed, the harder it got.

If I failed a level, I lost a life. Lose all five and I can either sit and wait, or simply pay. The button is green on purpose — because green means go. Or in this case: go broke.

But don’t have money? Go and beg your fake Candy Crush friends, that’s also an option.

If you sit idle for two seconds, don’t worry — Candy suggests a move. But that move might just be a trap.

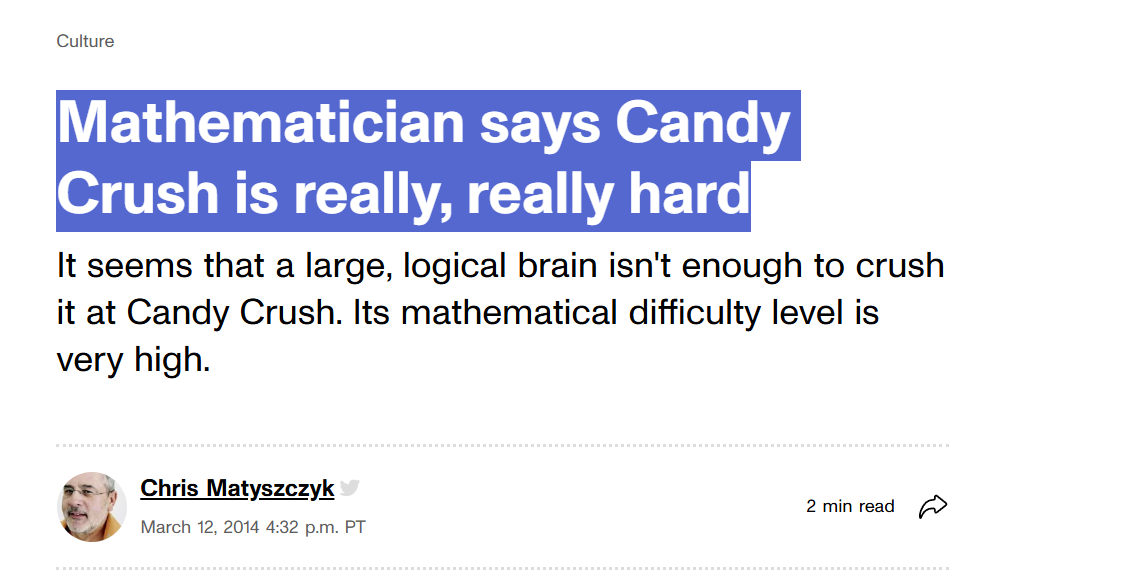

Even mathematicians say it’s really hard. Not just hard, but NP-hard — meaning not even a supercomputer could solve the game quickly.

And that’s the thing: You’re always so close. Every. Single. Time.

It’s called the near-miss effect, something to keep your brain juiced up on hope.

Basically what they do is train your brain to crave what it can’t have. A delay loop designed to keep you coming back. Classic conditioning.

And if you get bored? Don’t worry, the devs got your back — adding new levels, new candy, magic beans and jelly.

Oh, and of course, new mechanics. But not to be fun — to slow you down. Because slower means more attempts. And more attempts mean… more chances to pay.

It’s a Skinner box wrapped in sugar. Some are wrapped in Monopoly men and others in royal mascots or Pokémon. And it works.

People get hooked. Really hooked. Just google “Candy Crush addiction” and watch what auto-fills. No need to explain how bad it gets.

From spending 500, 1000, or 2000 dollars in a single day, people are addicted and begging for help — confused “how addictive a simple mobile game can be.”

In the media, Candy Crush was mocked, memed, and treated like a joke.

“People taking a dump everywhere can’t get enough of the app that’s as addictive as crack but far less rewarding.”

“Do you think the people making Candy Crush are even playing it? No, they’re just like MUAHAHAHAH.”

“Mario, don’t play that game. It’s not just candy. It’s evil! Evil candy!”

And other media outlets questioned the addiction problem more seriously.

“Some people are playing it for hours and might even be addicted to it.”

“Some people say they can’t put the game down.”

“Is Candy Crush on here? No, no! Keep walking! You’re an addict!”

While critics kept pointing fingers, King just smiled. With 90% of players never having spent a penny, they could hide behind numbers. But whenever they were asked about addiction… deflection.

Journalist: “[…] I have a couple of friends who are Candy Crush addicts, and they characterize themselves that way — they’re like, oh, I’ve got a problem, I’ve got to stop doing this.”

Zacconi: “Sure…well, I think that the - first of all - I think that the…I think that Candy Crush is a…is a…is a great game. It’s a fun game.”

Source (timestamped)

Also Zacconi:

“Fundamentally, games are fun — and fun is good for you.”

That’s King’s official stance. “Fun is good for you.”

Sure — why upset investors by admitting the game is just a Skinner box? Why admit anything if you can distract everyone… with marketing?

Oh boy do they have marketing. My favorite topic. Look at this.

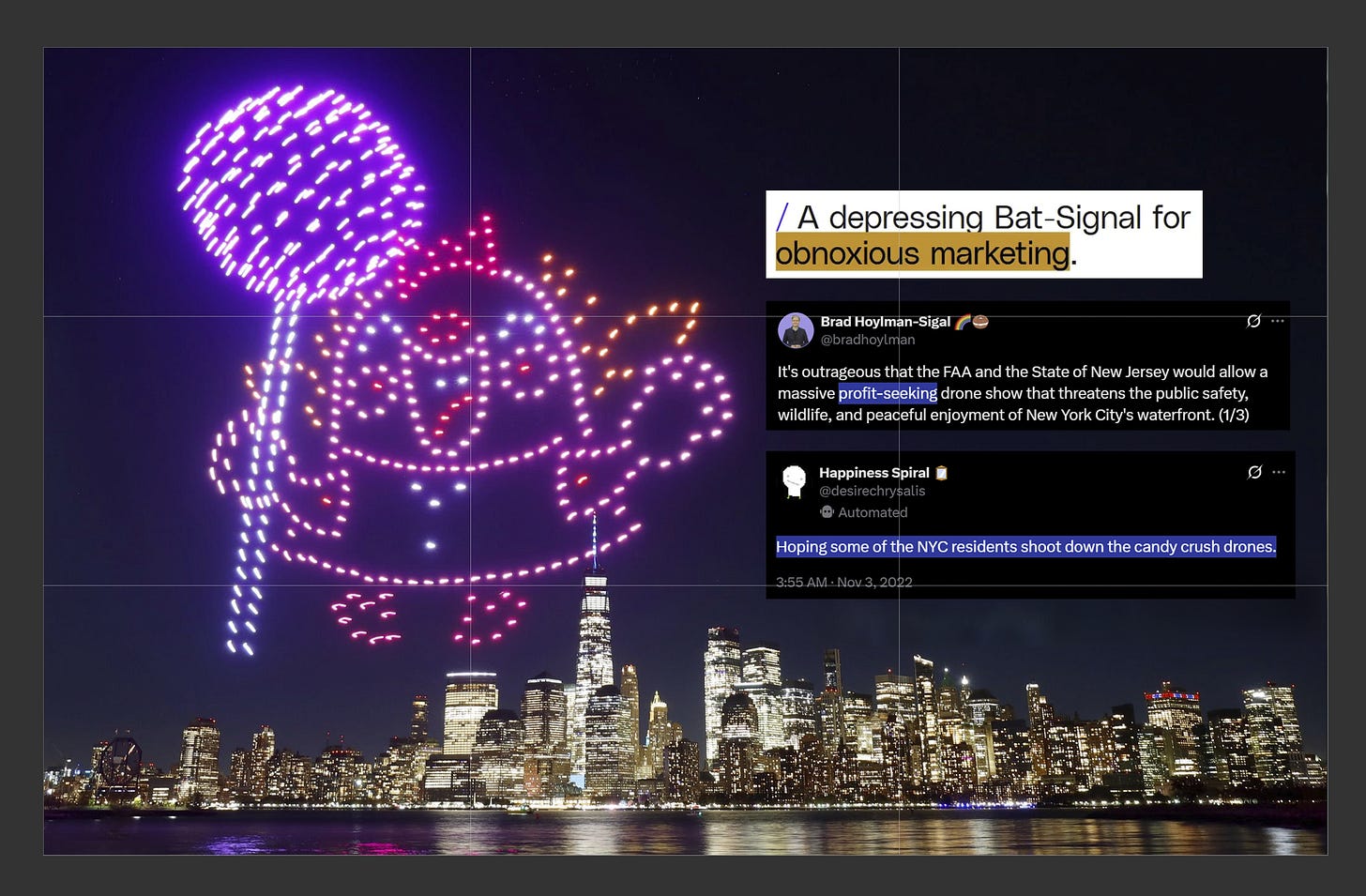

When I say marketing, I mean drones.

To celebrate Candy Crush’s 10th anniversary, King spammed New York’s night sky with 500 drones, turning it into a flying billboard. Locals called it “obnoxious,” the senator called it “profit-seeking,” and one literally tweeted, “Hoping someone shoots them down.”

But even if you shot them down, you’d just need to turn on the TV to see what’s going on there.

An actual Candy Crush game show.

Real players, in a real studio, playing Candy Crush on a giant wall. The prize? 100,000 dollars. The content? Watching people swipe candies for cash.

But if that’s not entertaining enough, how about reeling in a bunch of celebrities who probably don’t even play the game themselves.

And if you’re not into music, don’t worry — they’ve got purple soda flooding New York streets, or board game cafés in London, or billboards that candify all of New York.

Because apparently, the whole world is just one big level.

But billboards are boring. How about some immersive films where playing Candy propels you into the clouds, has you play upside down, or float through pink, sleepy dream worlds that “swipe the stress away.”

And once you’re really good at swiping your stress away, why not partake in Candy Crush’s million-dollar All-Stars tournament?

“Candy Crush has been my companion for more than 10 years.”

“I downloaded the game when I was sick with COVID, and couldn’t put it down.”

“And before you know it I found myself in this contest.”

“Crazy!”

“So crazy!”

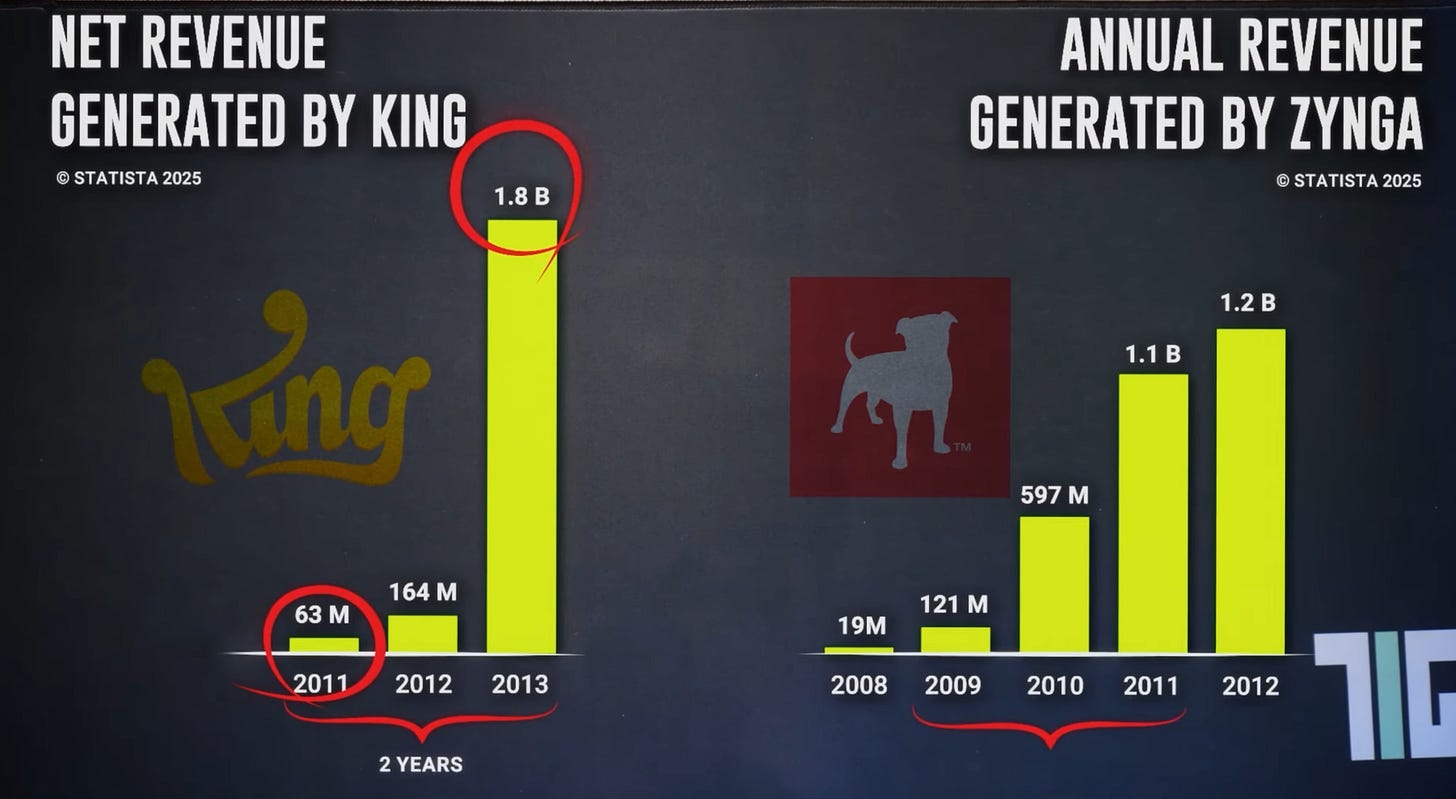

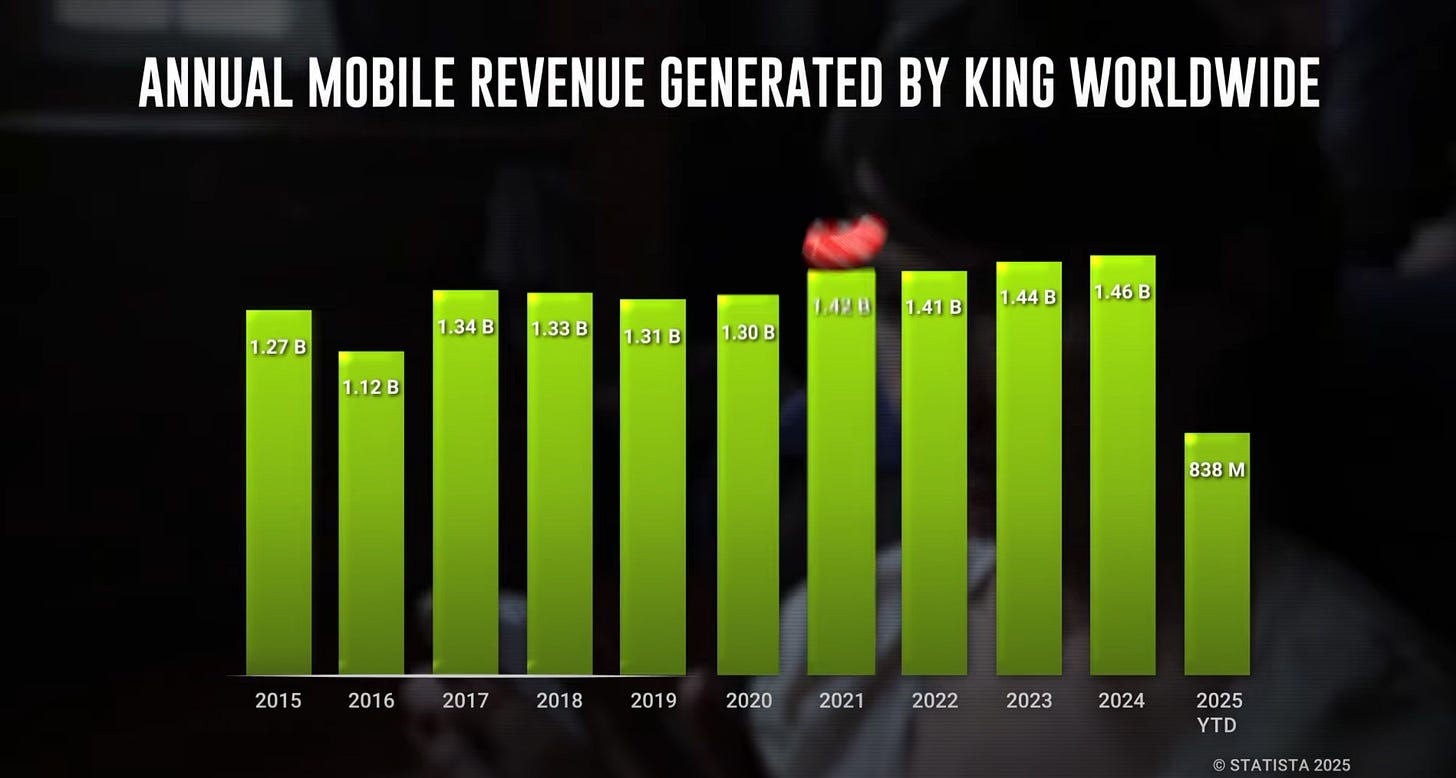

The marketing machine didn’t stop there. Commercial after commercial, the wiggling, jiggling, dancing, celebrity-endorsing, sweeter-than-ever marketing nonsense pumped King’s revenue from 60 million to almost 2 billion in only two years.

Only Zynga, the other mobile empire now owned by Take-Two, managed to grow this fast. I talked about Zynga’s crazy story here if you’d like to give it a watch.

Anyways, with 2 billion in revenue, it was time to take King – and its sharks – to its long-awaited throne.

Two years after Candy Crush launched, King went public, valued at 7 billion. Inside the New York Stock Exchange, candy mascots were dancing in a fanfare Wall Street had never seen before.

Riccardo would have probably preferred the mascot – because on that day, things didn’t turn out as sweet as planned.

“And it’s exactly like in the movies. You enter this room full with traders and it’s very narrow.”

Shares tanked 15%, making it the worst IPO debut for a newly listed company in the U.S.

But Riccardo had an answer. In his letter to shareholders, he pitched Candy Crush as “bitesize brilliance” – the perfect way to spend three minutes of free time, whenever, wherever.

In the end, it didn’t matter. While King’s stock flopped on day one, our sharks still became multimillionaires practically overnight. Riccardo, Mel, Seb, Thomas… except Toby.

He had sold his stake in King three years earlier to go and build something more ethical – Mangahigh, an educational math game for kids.

Ethical indeed, but not as lucrative. Because good ethics don’t ring the bell on Wall Street. Shady tactics do.

And just as King was cashing in, the lawsuits came knocking — from investors and from players.

Investors accused Riccardo of using “materially inaccurate” player data to inflate stock prices. And players sued King for quietly removing free lives — forcing users to buy more.

But deleting players’ lives was just the beginning. After targeting players, King came for indie developers.

“The makers of this super popular and addictive game have trademarked the word Candy.”

Yes. Candy — trademarked, just because they could.

CandySwipe came out two years before Candy Crush, with candy, swiping, and even the word “Sweet!” But to protect the bathtub myth, King flipped the script and accused CandySwipe of infringement.

And what can one guy do against a billion-dollar empire? Exactly. Nothing. All he could do was write an open letter:

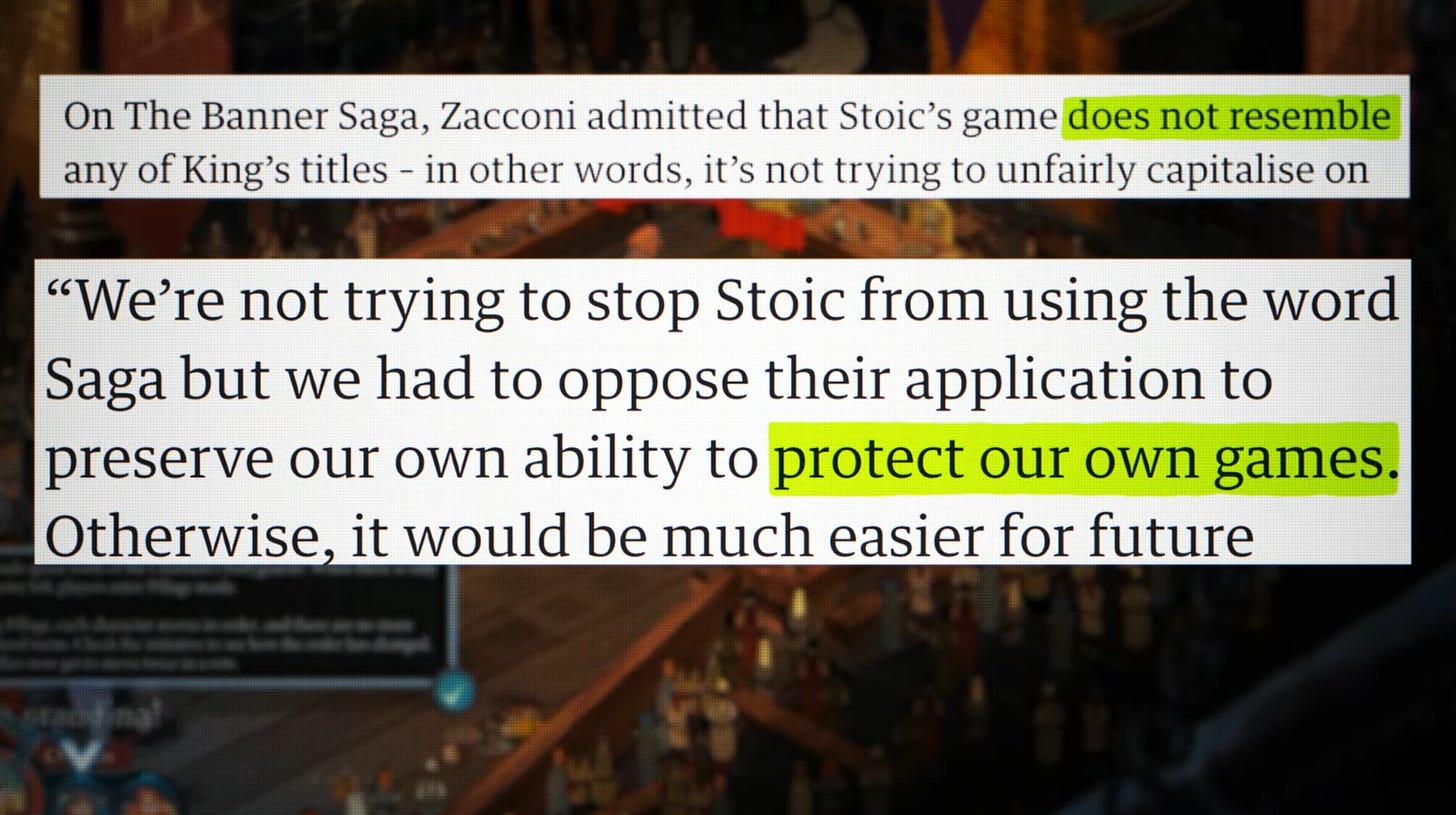

But King didn’t stop there. Next target? The Banner Saga, for using the word “Saga” — in a Viking game.

Even Riccardo admitted “it didn’t resemble Candy Crush,” but still tried to block the trademark “to protect their brand.”

But enough was enough. Indie devs fought back and launched the Candy Jam — a protest with over 400 parody games to mock King.

From Candy Fart Saga to Saga of Kersnuffle, the backlash got so big, King eventually backed down from trademarking “Candy” — at least in the U.S. In Europe, the word Candy is still trademarked.

Anyways, it’s good to know that a game about farting candy can still beat a billion-dollar bully.

But while indie devs saw a bully, someone else saw a cash cow. And that someone was Bobby Kotick.

CNBC: “Why this deal now? Why the maker of Candy Crush, and what does it do for Activision?”

Bobby: “Well, we couldn’t be more excited because it gives us an opportunity to participate in the fastest-growing game market in the world, which is mobile.”

After all the lawsuits, the mockery, and the market crash, Riccardo still found a buyer.

In 2016, Activision Blizzard dropped almost 6 billion to acquire King. Not for “mobile potential,” but for a billion-dollar tax dodge.

Activision had billions stuck offshore. If they brought it back to the U.S., they’d pay a massive tax bill. But if they spent it on an overseas company? No taxes. Same money. Same candy. So they used it to buy King.

And just like that, Candy Crush became a loophole.

While news anchors scratched their heads over the price tag, Bobby bragged about reaching “more than 500 million users.”

And Riccardo? He said this merger would “bridge all platforms.”

But in reality, it was a match made in spreadsheets. By 2022, Activision made more money from Candy Crush than Call of Duty.

And while one big fish was swallowing candy, another even bigger fish was already circling.

Well, it means Microsoft didn’t just buy Call of Duty. They bought the thing you play on the toilet that never stops making money.

On paper, it was about cloud gaming, the metaverse, and “future-proofing” Xbox. But in reality it was about owning the most addictive, data-rich mobile empire on Earth.

By 2022, Candy Crush was generating over a billion dollars a year, with margins even Call of Duty couldn’t touch.

And unlike console games, Candy Crush didn’t need hardware, development cycles, or even marketing. Just addiction and time.

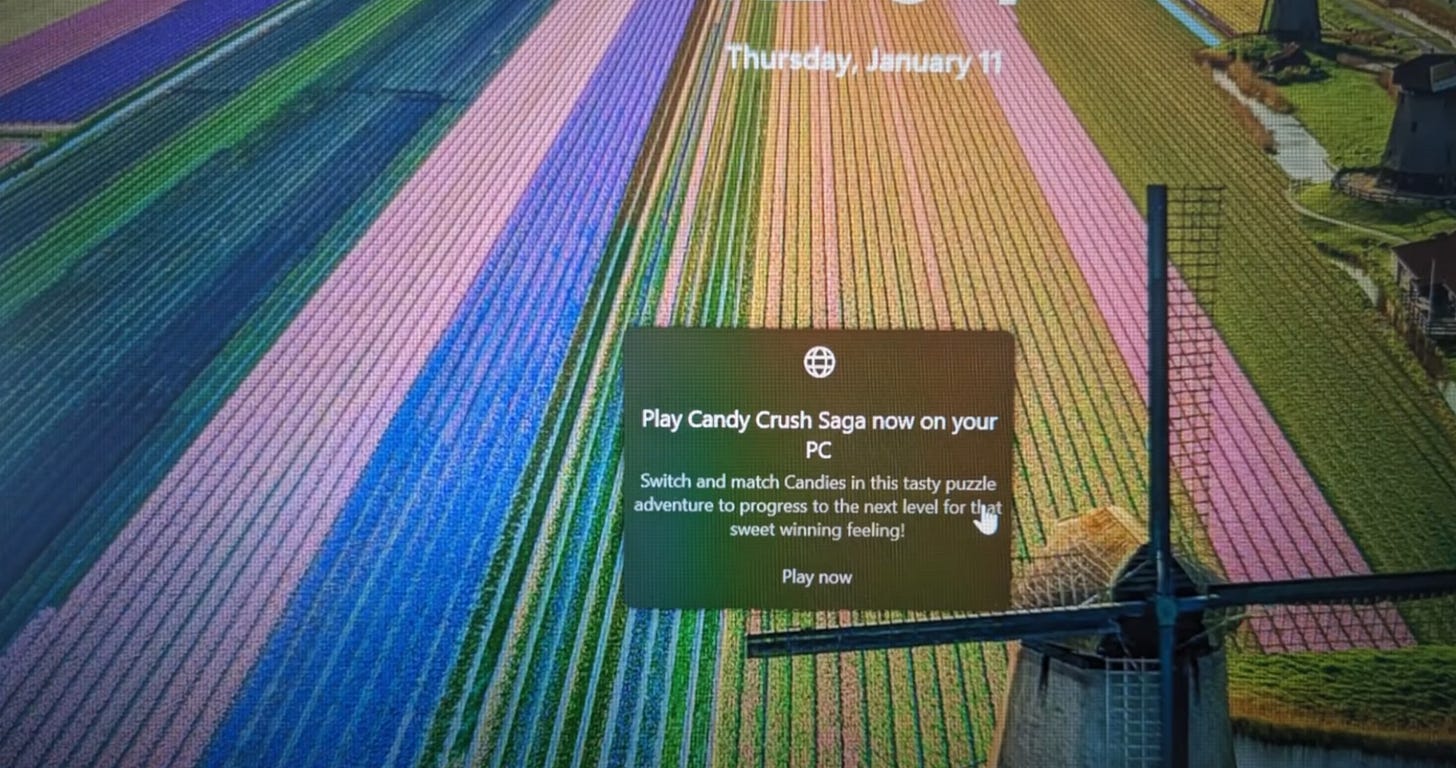

And once Microsoft owned it, things got creepy.

Users started seeing Candy Crush ads before even logging in — on corporate laptops, government computers, schools. It was “outrageously intrusive.”

And now, Candy Crush sits inside one of the world’s most powerful tech empires. Feeding data into Azure. Fueling AI experiments. Optimizing every tap. Every swipe. Every dollar.

And Riccardo? His “bitesize brilliance” is now feeding a trillion-dollar machine.

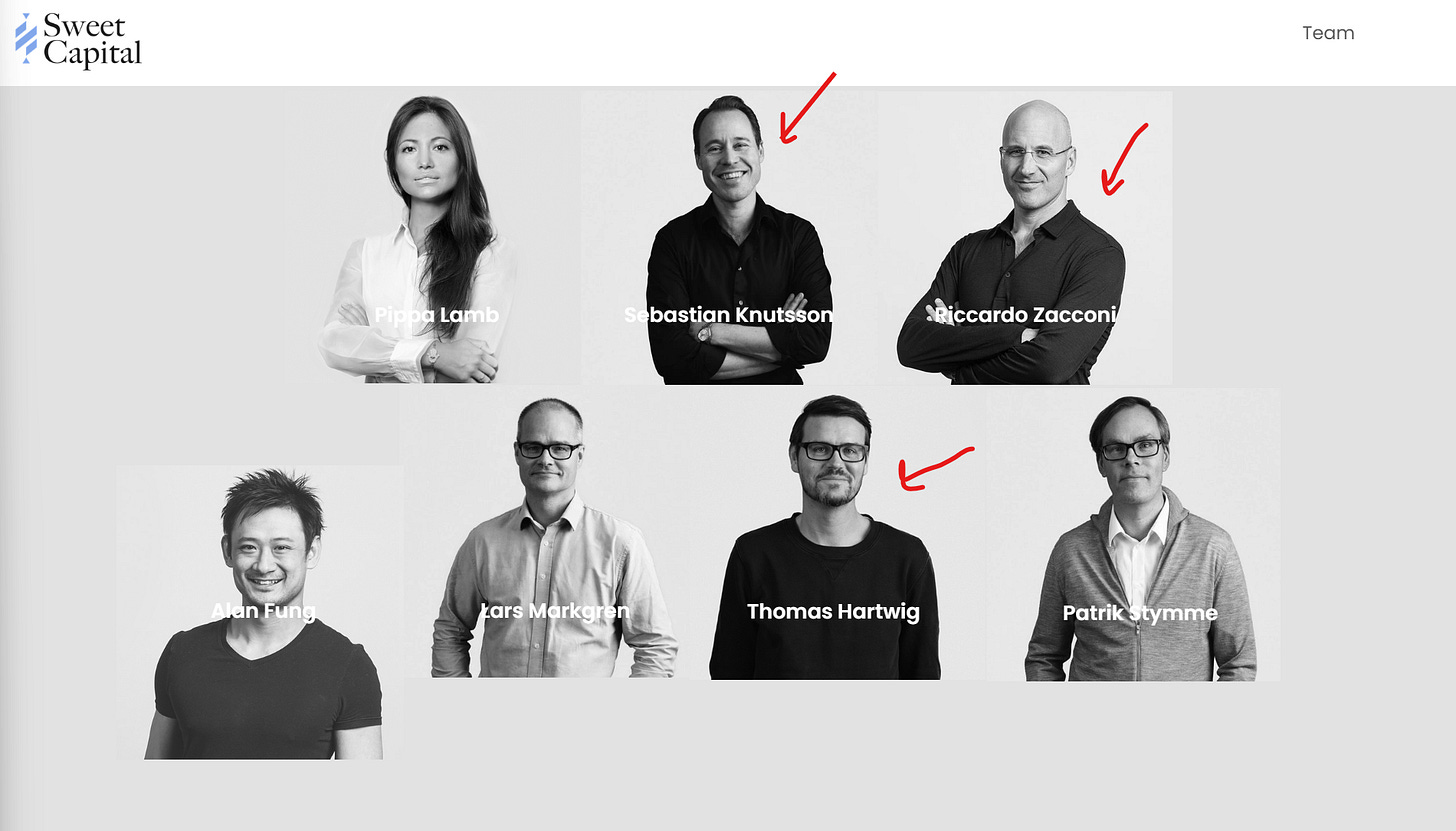

After nearly a decade of milking dopamine for profit, he stepped away in 2020 — along with Seb and Thomas — and started Sweet Capital, a VC fund now bankrolling the next generation of attention-grabbing apps.

In the end, King wasn’t built to make great games — it was built to be sold. Candy Crush was just the delivery system. The real product was a business model.

And now, that model is quietly replacing the art of making games. Not with games that move us, but with games that manage us. Predictable. Profitable. Repeatable.

I do wish I could say creativity will win. But right now, the one that wins is the one that monetizes faster.

And that’s the future we’re drifting into. One where Candy Crush founders get richer than GTA creators.

Source: IGN